Sulufou – An Artificial Island with Rich History

BY MIKE TUA

A recent trip to Sulufou artificial island by Sunday Isles has given us the access and opportunity to experience life on the artificial island firsthand.

Sulufou is known to many as one of the largest, oldest, and most densely inhabited artificial islands in the Lau Lagoon of Northeast Malaita. There are hundreds of families and about 300 people living there.

Known as the “Salt Water” or “Solwata” (in Pidgin) people, Sulufou was built by bare human hands with skills that have been handed down from one generation to the next until today. It is evident to say that the knowledge and skills of island building and several other traditional arts that are still kept in practice on this amazing and unique artificial island in the Solomon Islands.

Sulufou Island has arguably one of the most interesting human histories of all of the artificial Islands in the Lau Lagoon of Malaita province in the Solomon Islands archipelago.

As an artificial island built on the reef in the Lau Lagoon, Sulufou is famous for surviving a Scottish seaman known as John (Jack) Renton.

“Renton is the only survivor among five deserters from the American guano ship Renard in 1868,” according to Emeritus Professor at the University of Queensland, Clive Moore, in his book, “Making Mala’.

“Renton and his companions drifted almost 2,000 kilometers in one of Renard’s boats before landing at Maana`oba Island off the northeast coast of Malaita. His four companions were killed and Renton was taken to Kabbou, a Lau Lagoon big man on Sulufou artificial island, where Renton lived from 1868 until 1875.

“It was during this period that labor recruiting vessels out of Queensland and Fiji initially ventured to Malaita, the first arriving in late 1870 and early 1871. In August of 1875, Renton was rescued by the crew of one of these, the Queensland ship Bobtail Nag.

“Renton learned the Lau language and participated in life on the lagoon for eight years, and there are indications that he developed close relationships, yet the account he left us is disappointingly shallow. He returned to Malaita as an interpreter on a recruiting ship in late 1875 with gifts for his adopted family, but he never visited the island again and died in 1878. One thing Renton helped to bring about was the rise of Kwaisulia, the leading Lau passage master (the ‘in-between’ men who controlled the interface between the labor recruiters and potential laborers) from the 1880s until the 1900s,” described by Making Mala.

Sulufou was also famous for the country’s historic and tragic village fire which happened in 1958.

“Every house on crowded Sulufou artificial island in Lau Lagoon, Malaita was destroyed by fire in fifteen minutes on 6 July 1958. Seventy-three houses were destroyed, five hundred people were left homeless, ten were badly burned, and one child died. The village was rebuilt, and when St. Paul’s church was reopened there in January 1963 two thousand visitors and the Sulufou population of 1,500 attended a three-day feast at which 104 pigs were killed. In 1967, a fund was established to build permanent houses on the island,” according to the Solomon Islands Historical Encyclopaedia 1893-1978.

For years, the island of Sulufou holds the country’s protectorate history as the tiny loyalist island in which her inhabitants have compulsorily practiced raising the large Union Jack flag daily from a high flagpole, late Chris Cochran (British Administrative Officer, Solomon Islands 1967-1982) noted in his writings.

The large Union Jack flag daily from a high flagpole in front of the Saint Paul’s Anglican Church at Sulufou, Northeast Malaita. Photo by John Hounihau

According to the late Chris Cochran, in 1944, at the end of the war in the Pacific, Solomon islanders rebelled against the return of the British to rule them, preferring the Americans with their anti-colonial opinions and masses of cargo given to the islanders, with promises of more to come. A potent mix.

“Starting in Malaita and fanning out to neighboring islands, Britain lost most administrative control except for judicial services, which the rebels wanted us to continue to provide. However, one small artificial island in the Lau Lagoon, of just 300 people in the rebel-heartland island of Malaita of 50,000 withstood the pressure to conform to the rebellion. Sulufou, the tiny loyalist island, flew a large Union Jack daily from a high flagpole. As the rebels canoed past Sulufou they exchanged verbal insults such as “Inpoo” (meaning “big man”), implying they were nothing, a tiny number in the mass of rebels. There was no cooperation at all, and general surliness, except on this one small artificial island of Sulufou. The people there made it very clear they did not want to return to the old ways of magic, customs, and inter-tribal wars. They wanted peace and development.

“Their Leader, Wate, displayed great shrewdness and vision to see there was no going back to the old ways. A small man of great stature and wisdom. A giant amongst dwarves.

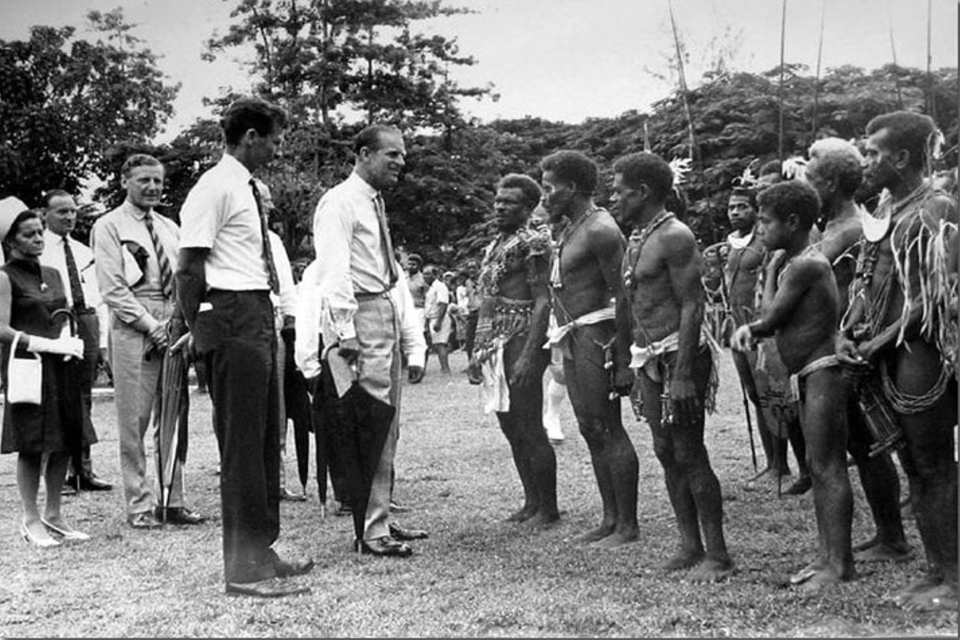

“As for the one loyalist village. It profited immensely, as Wate wanted, living off its loyalty too, reminding anyone of it who would listen. They were immensely brave to remain loyal in a sea of rebellion. Their old flag of defiance remains to this day; moth-eaten, torn, and ragged; a gentle reminder of their loyalty to the Crown. They are repaid with a Royal Visit every time royalty is in town, especially the Duke of Edinburgh, who must know it well from several personal visits. They are very upset that he is retiring and not returning.

“But the Marching Rule legend lives on to this day, with both sides very proud of what they did and endured from 1944 to 1955/56,” the late Chris Cochran stated in his writings.

Sulufou Today

Today, residents of Sulufou are faced with the harsh reality of climate change coupled with social, environmental, and development problems, according to cited reports on Sinking Islands, Drowned Logic; Climate Change and Community-Based Adaptation Discourses in the Solomon Islands published in 2020.

“The majority of Sulufou residents have abandoned their artificial island due to fear of natural disasters (cyclones), lack of access to education, healthcare, sanitation and roads, water scarcity, saltwater intrusion ‘rising sea-level and king tides’, land disputes, unemployment (out-migration), lack of agriculture development and impacts of overfishing (threatening their rural livelihoods and food security).

“The rise in sea levels and erratic weather patterns make these islanders no longer safe in (their) homes so intimate with the sea. As a result, the residents have no choice but to flee the ever-deteriorating impacts that climate change has brought on their island environments,” the report stated.

Likewise, SUNDAY ISLES travel journalist, John Hounihau recently visited Sulufou and described: “On Sulufou, it’s quite hard to see any tangible signs or aspects of development making progress, there are more gaps on the ground that needs more urgent improvement.”

“The residents of Sulufou have said there is no running water taps on Sulufou, the rural residents normally fetch water for drinking and cooking from rainwater storage tanks and often paddle their canoe or travel on an outboard motor to the mainland to access water from freshwater springs.

“Years of unresolved land disputes have prevented the Sulufou community from accessing a running water supply.

“The residents mainly rely on the Gounatolo Rural Health Clinic and Community High School which is situated in the Fouia community on the mainland [just opposite the island of Sulufou] to access key health care and education services.

“The residents have also said that they have unusually experienced king tides on several occasions. The high king tides have flooded their community and have allowed them to paddle their canoes through the village.

“They say the king tides even reached the footsteps of the St Paul Church in Sulufou,” John described.

Anglicanism (Church of Melanesia) is the only denomination in the Sulufou, which represent 100 percent of the Island’s population.

Hopes for Tomorrow

There are still many historical and cultural landmarks to be discovered on the Sulufou artificial Island.

The Island holds the potential to become a future tourist destination in the country, the rich history, tradition, and culture of the island have yet to open up for both local and international visitors – they would be surprised to learn new depths of understanding of Malaitan history, kastom, Colonialism past, and Maasina Rule.

Likewise, Sulufou is also described in Walter G. Ivens’s book, The Island Builders of the Pacific (1928), and in Nigel Randell’s book, The White Headhunter (2003) (about Jack Renton who lived there as an Islander for seven years in the mid-1800s when shipwrecked and also the island is known for two royal visits by the Duke of Edinburgh, late Prince Phillip (husband of late Queen Elizabeth II).

John Hounihau noted: “With all I see, Sulufou is a potential, historical and cultural spot for tourism attraction, they have a good leadership structure in place, I think and believe if they work together, share ideas for a common goal, it will improve the lives and long-standing issues experience by the islanders.”

Nevertheless, John has championed Sulufou’s past and current generations as the most resilient, patriotic, and resourceful people in the Solomon Islands.

“The challenges, struggles, and commitments faced by the saltwater people of Sulufou are a real testament to their success today, and despite the adversities of life which they’ve encountered over the years, it’s interesting to know the island had raised many scholars, lawyers, doctors, economist, national soccer players, musicians, priests and you name it in both the formal/informal sector of employment in the Solomon Islands,” he commented.